The Idea

JavaScript is everywhere! Almost every device we use today is connected to the Internet and supports JavaScript by its runtime environment. But in the same way new devices arrive on the market, old software written in plain old Java is still alive and useful. The idea is now to bridge the gap between this shiny new JavaScript world and our old but still useful legacy software written in Java.

Why do I need this and why did I write this?

This idea is not new. There are a lot of Java-to-JavaScript transpiler frameworks available. The most popular of them is GWT, the Google Web Toolkit. GWT is a Java-Source to JavaScript Transpiler. To use GWT, we need the original source code of the system we want to port to JavaScript. Then we have to annotate it with GWT module definitions and finally have to pass it thru the GWT compiler to get the desired JavaScript.

GWT works pretty well. The major problem is the fact that we have to modify the original source code to make it work. A minor problem is the tooling behind GWT. The compiler is very slow.

But what are the alternatives? How can we get rid of modifying existing source code?

Well, the idea is now not to use the Java source code to transpile it to JavaScript. We use the JVM byte code! The byte code is the result of the Java compilation process, it is the .class files. Fortunately the byte code is very compact and easy to read. And even better: it is easy to process, as internally the byte code describes a stack machine which is used to do all the data processing and heavy lifting. Using the byte code allows us to compile running applications without modifying their source code. And it also allows us to compile other languages, we can basically handle every language that compiles to JVM class files. This enables some very interesting migration scenarios, we are no longer limited to Java source code.

Stack machines are known to be low-level, very compact and have a limited instruction set. But this compact format has a downside: JavaScript is not a stack machine, JavaScript as a compile target is a high level language. So we basically have to write an inverse compiler. We compile a low level language such as the JVM stack machine to a high level language such as JavaScript. This is the exact opposite of what a normal compiler does: compiling a high level language to machine language.

Now, why should we implement our own compiler? There are a lot of frameworks available outside, but only a few can interpret and transpile byte code. There is a gap that should be filled. Another reason is education and fun. Writing a compiler is a completely different task than writing web services with Spring MVC or doing some JDBC queries. Compiler design is much more complicated and much more low level. So it is a very interesting challenge!

It you want to checkout the results of this experiment, please visit the GitHub Project Page at https://github.com/mirkosertic/Bytecoder.

Where to start?

Writing a compiler is a science and also an art. Compiler include almost every concept known to computer science, starting from parser generators to control flow constructs, data structures such as linked lists and finally CPU architectures, memory management and register allocation.

Doing this all at once is far too complex. We have to split this complex problems into smaller ones. And we start with a very small one: parsing JVM class files.

Class files are very good documented, and reading them is a simple task. The interesting point is here: what do we read, and where do we start? A JVM program itself has some dependencies, as it will of course use code and classes presented by the class lib. This library contains thousands of classes and even more methods. It would be a waste of memory and computing time if we would parse the whole class lib. So we start at a given entry point such as a „main“ method, and only include used classes and methods that are required to be linked. We continue to resolve dependencies until we have everything required to run the program. This will help us in two ways: we get a class and method dependency tree which is needed in other steps in our compilation pipeline, and the dependency tree only includes required classes and methods. Downside of this static code and dependency analysis is that it cannot support the Java Reflection API properly. Since we only know what classes are instantiated and used by the new operator, we cannot catch usages of the Class.forName().newInstance() API and other Java Reflection use cases. This is OK as most of the source code I want to compile to JavaScript does not use reflections.

Finding the right blocks

After we have read the Bytecode and constructed the class and method dependency tree, we have to analyze the method implementations and their control flow. Analyzing everything at once, finding variable usages, handling branching and loop conditions correctly can be very complicated. Fortunately there is a solution available for this task. Prior to any data flow analysis, we divide the program into so called basic blocks. Basic blocks are branch free lists of instructions, with a single entry point and a single exit. Finding basic blocks is an easy task. We just have to iterate over the Bytecode instructions. Every branching instruction (GOTO, INVOKE, RETURN, IFs etc.) starts a new basic block.

Now we have a set of basic blocks and know their dependencies. We have a control flow graph. We can now continue do parse every single basic block and create an intermediate representation from the containing byte code. This intermediate representation is basically an abstract syntax tree with single static assignment as a property. Single static assignment or SSA means that for every variable there is only one declaration and only one assignment. Every variable is a constant, and every computation becomes pure functional!

Generating the intermediate representation from the JVM stack machine

Transforming the JVM stack machine code into an intermediate representation is a complex task. The byte code is basically a mixed stack machine. We have a stack, and we also have a list of local variables for values that are frequently used. Consider the following example byte code:

ILOAD_1

ILOAD_2

ADD

ICONST_2

ADD

RETURNThis basically pushes local variable with index 1 and 2 on the stack. Then it performs an addition, which pops the two values from the stack, and pushes the result onto the stack. Another addition is done by pushing the constant value 2 on the stack and adding it to the previous result and pushing the result on the stack. Finally it performs a return, which pops the addition result from the stack and returns the value as the methods return value.

To convert this stack code into the intermediate representation, we have to run it thru an interpreter. This interpreter has ist own stack and local variables. But it does not do any computation. It just tracks where every stack or local variable came from, what happened to it and where it went. It traces the whole data flow inside our basic block. For the byte code above, the following intermediate representation is generated:

const variable1 = @local1

const variable2 = @local2

const variable3 = variable1 + variable2

const variable4 = 2

const variable5 = variable3 + variable4

return variable5Let me explain. Every push operation on the stack created a new variable with the pushed value as its assignment. We see that variable1 is initialized with the reference to the local variable with index 1, described as @local1. The same happened to @local2 and also to the constant value. We can also see what happened to the two addition operations and what is finally returned.

This example shows what SSA form basically means. We have a set of constant values and a set of functions, which performs computation on these values without side effects. We have created a completely functional representation of the stack machine code! Creating a SSA form gives us the ability to perform reasoning about the program flow much easier as it would be using the original stack machine code.

SSA form introduces a lot of new variables. This is OK, as we rely on optimizing logic which is run in later steps of the compilation pipeline to get rid of some of the variables. For now we use this a little bit redundant form for easier reasoning and processing.

Some naming trickery must be done for control flow constructs such as loop. The loop counter for instance is incremented multiple times, depending on how often the loop is executed. This is a problem, as SSA form insists on one declaration and one assignment. If we take a look at a simple control flow graph of a loop, we see that the loop body is its own predecessor, and in fact it has two.

Now we introduce a new concept: the PHI function. A PHI function can be used as an assignment for a variable, and PHIs value depends on the predecessor of the current basic block in the control flow. The PHI functions are placed at the very beginning of each basic block. So for the above control flow graph, the assignment of the loop counter basically looks like

const loopcounter = PHI(B -> initialValue, D -> loopCounter)This means that if we are coming from B, loopCounter is assigned to initialValue. If we are coming from D, loopCounter is assigned to itself.

PHI functions look a little bit weird. But they are a nice trick to keep the single declaration and single assignment rule hold true. Don‘t get confused by the name „PHI Function“. A PHI Function is not compiled to any function code at all. It is basically used as a placeholder for a register or memory location which is accessed from multiple basic blocks, nothing more.

Optimizations

This compiler does not perform advanced or very sophisticated optimizations. Instead it relies on tools which can perform this task(I‘ll come to this later). To generate fast and efficient JavaScript, we basically have to do two steps that cannot be done by other tools. We have to de-virtualize method calls and recreate JavaScript control flow constructs from the low level byte code.

De-virtualization has a major performance impact on generated code. By default every non-private non-static JVM method call is virtual. This means that the runtime has to search for every method call the right method implementation. This lookup is done using virtual method tables for every class. This lookup is a major performance bottleneck. Most of the time, a virtual call is not necessary, as there is only one implementation for a method available. So this virtual method call can be replaced by a direct method call. Since we already know the dependency graph for our classes we are compiling, it is easy to find out which methods require a virtual method call, and which not. The JBox2D example I will present later shows that ~80% of all virtual method calls can be replaced by a direct method invocation.

The second major performance improvement can be archived by control flow construct recreation. At JVM byte code level, we only know conditional or unconditional branches. Without control flow recreation, this branches must be emulated as shown in the following example code:

FLOATabsFLOAT : function(p1) {

var var0 = null; // type is FLOAT

var var1 = null; // type is FLOAT

var var2 = null; // type is INT

var var3 = null; // type is INT

var var4 = null; // type is BOOLEAN

var var5 = null; // type is FLOAT

var currentLabel = 0;

controlflowloop: while(true) {switch(currentLabel) {

case 0: {

var0 = p1;

var1 = 0.0;

var2 = (var0 > var1 ? 1 : (var0 < var1 ? -1 : 0));

var3 = 0;

var4 = var2 >= var3;

if (var4) {

currentLabel = 9;continue controlflowloop;

}

}

case 6: {

var5 = (-var0);

return var5;

}

case 9: {

return var0;

}

default: throw 'Illegal state exception ' + currentLabel;

}}

}Most JavaScript runtimes cannot handle such code in a performant way, as they are optimized for „normal“ JavaScript loops using for and while statements. This can be fixed by doing some pattern matching on the control flow graph. We are searching for common patterns such as IFs, FOR and WHILE blocks and try to recreate the original control flow from the byte code in the intermediate representation. The result of this process looks as follows:

FLOATabsFLOAT : function(p1) {

var var0 = null; // type is FLOAT

var var1 = null; // type is FLOAT

var var2 = null; // type is INT

var var3 = null; // type is INT

var var4 = null; // type is BOOLEAN

var var5 = null; // type is FLOAT

var0 = p1;

var1 = 0.0;

var2 = (var0 > var1 ? 1 : (var0 < var1 ? -1 : 0));

var3 = 0;

var4 = var2 >= var3;

if (var4) {

return var0;

} else {

var5 = (-var0);

return var5;

}

}The control flow re-creator is in an early stage of development. It works well for easy cases. If it cannot recreate the control flow properly, it performs a fallback to unoptimized code.

Targeting the compiler to JavaScript

Compiling the intermediate representation to JavaScript is the final act in the compilation pipeline. The code generator is basically a tree walker for the abstract syntax tree of the intermediate representation, which generates JavaScript.

The tricky part here is the shape of the generated JavaScript. For my compiler I do not use any of JavaScript object oriented features. There are two reasons for that. One reason is that JavaScript does not differentiate Classes and Interfaces the same way JVM byte code does. Functionalities such as instanceOf checks and constructor chaining, constructor overloading and runtime classes must be emulated somehow. The other reason is performance. JavaScript uses prototype based inheritance, which means that the runtime has to traverse the whole prototype hierarchy for object field access in the worst case. Since the compiler knows in every case how to access an objects property, this lookup is a little bit redundant.

So basically we end up with JavaScript code like this:

// This is the Java Class

var LoopingTest = {

// A class has static fields

staticFields : {

name : 'de.mirkosertic.bytecoder.core.LoopingTest',

},

// And also a runtime class

runtimeClass : {

jsType: function() {return LoopingTest;},

clazz: {

resolveVirtualMethod: function(aIdentifier) {

switch(aIdentifier) {

default:

throw {type: 'unknown virtual name'}

}

}

}

},

// Each method has an unique identifier, generated by the compiler

// This is the virtual method lookup table

resolveVirtualMethod : function(aIdentifier) {

switch(aIdentifier) {

case 0:

return LoopingTest.VOIDtestSimpleSum;

default:

throw {type: 'unknown virtual name'}

}

},

// Code to implement the static class initializer

classInitCheck : function() {

},

// Create a new instance of the class, the new invocation

emptyInstance : function() {

return {data: {

}, clazz: LoopingTest};

},

// The unique type identifier of this class, generated by the compiler

thisIdentifier : function() {

return 2

},

// Check if this class is of a specific type, here the generated type identifier are compared

// this is used to implement instanceOf checks

instanceOfType : function(aType) {

switch(aType) {

case 0:

return 1;

case 2:

return 1;

default:

return 0;

}

},

// A instance method implementation

VOIDtestSimpleSum : function(thisRef) {

// Method body goes here

},

}And that is it.

A simple Demo: JBox2D Physics simulation

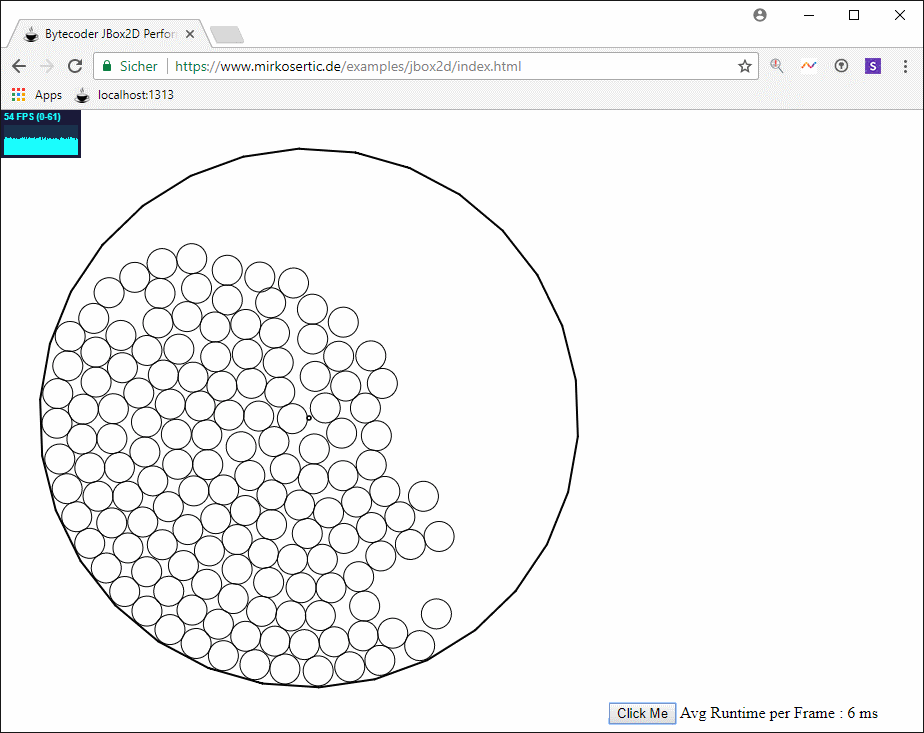

Ok, now let’s see if the compiler is working and check the correctness of the compilation process. I chose a simple JBox2D simulation, written in Java. This is a nice example, as it includes complex control flow, complex computation logic and also some nice visual feedback.

And here it is, the running JBox2D Java Program transpiled to JavaScript:

Going further and Optimization

As I mentioned at the beginning, this compiler experiment is written for efficient translation between JVM byte code and JavaScript. It has some build in optimizations such as de-virtualization and loop re-creation, but nothing more. This gap should be filled. I could implement a lot more optimization logic into the compiler, but due to lack of time, I want to show you another option. Let me introduce the Google Closure Compiler. The Closure Compiler translates JavaScript to more efficient JavaScript. This sounds simple, but is a very complicated task. Given the JBox2D example from above, the Closure Compiler gives us the following results:

Metric | Size of generated code | Compile time |

Bytecoder JBox2D example | 6355781 bytes | 1.470s |

Google Closure Compiler | 905094 bytes | 13.256s |

The closure-compiled version was ~20% faster during the JBox2D benchmark.

From my point, this is a viable solution to do further optimizations of the generated code.

Final words

Writing this compiler was an interesting challenge and a lot of fun. It gave me a deeper understanding of JVM, JavaScript performance characteristics and opportunities for code re-usage. I would be really glad if the results are in the same way useful to someone else as they were to me. Thanks for reading!

Git revision: cc97959